The Benchmark Imperative

… But first, the news:

… But first, the news:

India plans to roll out AI as part of its national curriculum. India’s Ministry of Education announced that AI will become part of the curriculum from Class 3 through secondary school, and in undergraduate engineering and business programs, by 2026-27. The government is also testing AI-powered EdTech: Chandigarh has initiated the development of an E-learning platform to teach Punjabi, using AI for adaptive learning and remote assessments.

African governments turn to AI to tackle public-sector challenges. The DRC has launched a five-year, $1 billion digital transformation plan and National AI Strategy, featuring a new Congolese Academy of AI for education, agriculture, and health. UNESCO and the KIX Africa 21 Hub are also supporting Benin, Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, and Senegal in developing teacher and student AI competency frameworks and local-language digital resources. Rwanda is setting up an AI scaling hub with a $17.5 investment from the Gates Foundation.

Frontier models deepen their commitments in Africa and India. Google will train 1 million civil servants across Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, and Brazil on AI policy, ethics, and implementation. In India, it has committed $15 billion to a new AI hub in Visakhapatnam, with data centers, fiber expansion, and a subsea gateway. OpenAI is also partnering with the University of Lagos to launch an AI academy for students and researchers.

Building evidence for EdTech in the age of AI

In medicine, no treatment launches without years of trials and evidence. In space exploration, every failed rocket is just R&D with more drama. Education sits somewhere in between. It craves bold innovation, but when we skip testing, we risk burning through time and money on shiny ideas that flop.

This is not just a challenge in the Education sector, though. Across the development sector, the question has shifted from “do AI tools work?” to “how do we test them systematically?”

Organizations like the Center for Global Development, IDinsight, and Precision Development are already experimenting with faster, more practical ways to generate evidence, blending user-centered design with a bit of startup agility. There’s growing appetite for shared benchmarks, but also a healthy awareness that numbers alone don’t guarantee impact.

The sweet spot? Evidence that’s built early, often, and collaboratively – fast enough to keep up with tech, but grounded enough to matter.

Common misconceptions we often hear:

“AI moves too fast for evaluation.”

“Bigger models are always better.”

“Closed models guarantee safety.”

“High benchmark scores equal real-world impact.”

These ideas still shape too many conversations and they deserve a reality check!

Creating evidence: Why benchmarks & evaluations matter

Benchmarks and evaluations try to answer the million-dollar question: What does good AI-powered EdTech look like?

“AI benchmarks can provide some guidance on how well different models and products can perform certain tasks. This can be a useful signal to help inform decision making, both for end users, evaluating educational AI products, but also for builders developing AI products to compare between underlying foundation models.”

In plain terms, benchmarks test whether an AI model can actually do what it says on the box. They run different tools through the same challenge, using the same scoring rules, so you can tell who’s really delivering and who’s just talking a good game.

Evaluations, on the other hand, show how those benchmarked tools behave in the wild – in real classrooms, with real teachers and real connection issues. Do they improve learning? Do they make teachers’ lives easier?

The strongest evidence stacks these steps together: context-specific benchmarking, quick field pilots, and honest feedback from teachers and learners. It's a fast, low-cost test of what actually works before scaling the hype.

Once a product’s been tested in both the lab and the classroom, decisions about scaling get a whole lot easier (and smarter).

Benchmarks: Our first stop

In a fast-moving AI world, benchmarks are our compass, helping us figure out what “good” actually looks like.

We see benchmarks everywhere. The Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings rate universities across 18 indicators, and Wirecutter tests blenders and earbuds so we don‘t have to. The same logic applies to AI, just with higher stakes.

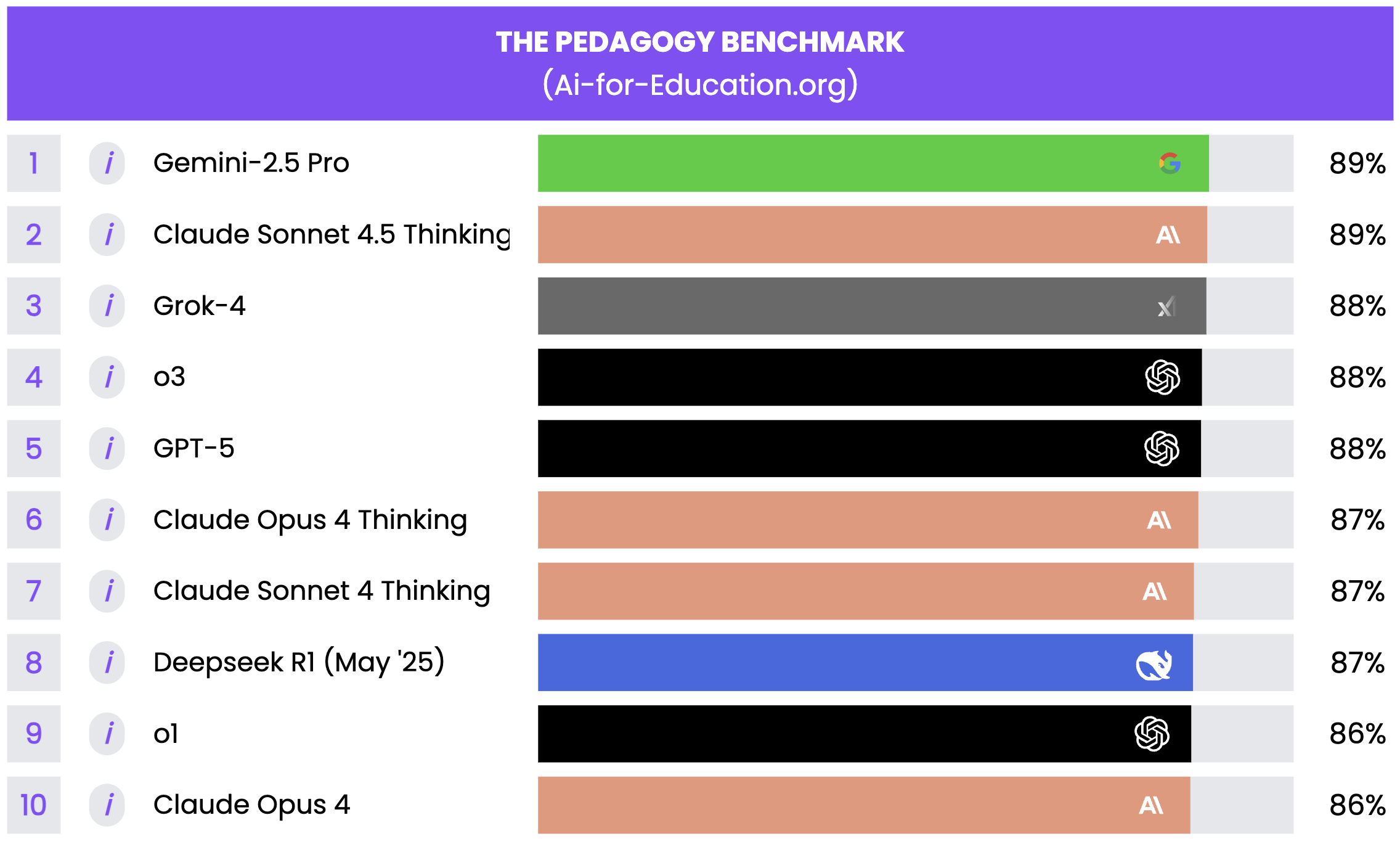

A benchmark is only useful if it mirrors the tasks the AI will actually perform. The Pedagogy Benchmark, for example, shows that a model can ace reasoning tests yet totally blank when asked to explain long division to a third-grader.

In education, effective AI depends on more than raw reasoning. It needs a mix of:

Pedagogical understanding – can it “teach” well?

Content alignment – does it accurately reflect the curriculum?

Assessment quality

Ethics and bias safeguards

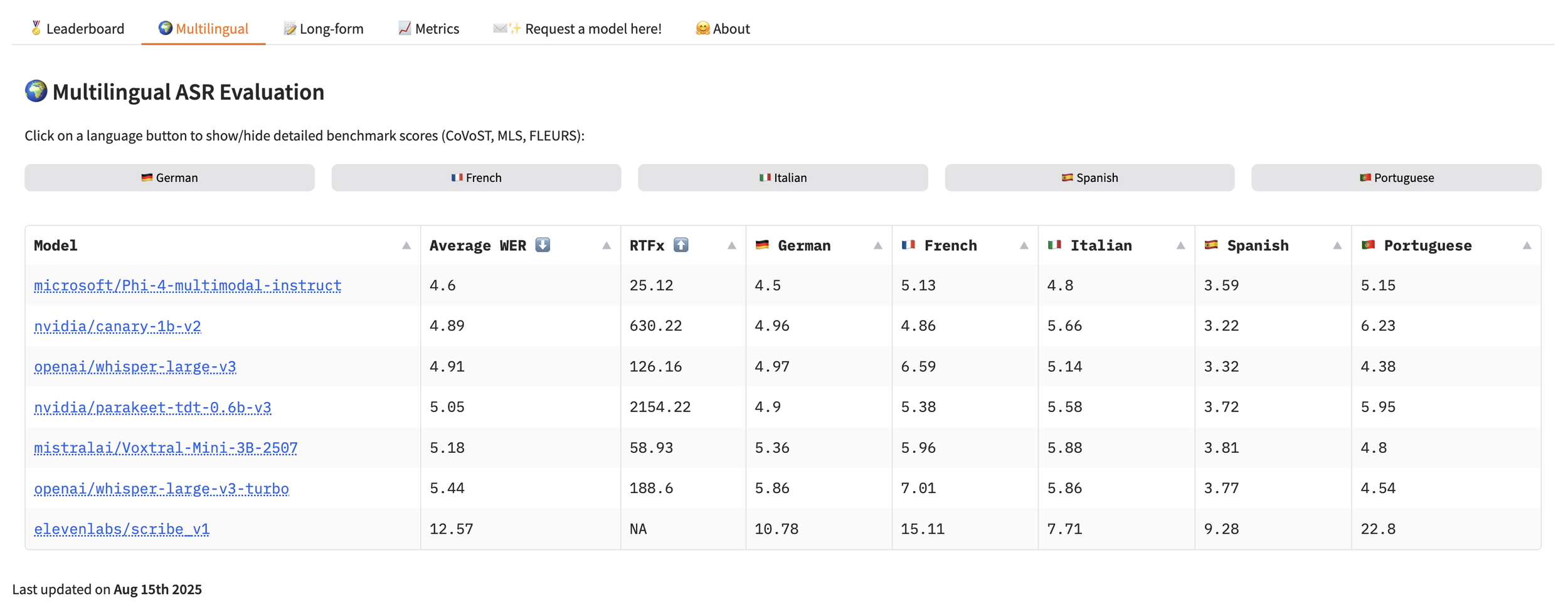

Accessibility and multilingual performance

Together, these dimensions show why context matters. Here’s a glimpse of how different AI models perform on pedagogy and multilingual benchmarks – a reminder that “top scoring” models aren’t always the best classroom performers.

(source: The Pedagogy Benchmark from AI-for-Education)

(source: The Open ASR Leaderboard on the Hugging Face Hub)

Evaluation in practice: Measuring what matters

Evaluating AI in education isn’t just about test scores or fancy dashboards - it’s about how tools hold up in actual LMIC classrooms and communities.

A solid evaluation looks at 5 things:

Learning outcomes: Does it really move the needle on literacy or numeracy?

Cost effectiveness: Are the learning gains worth what we’re spending?

Teacher trust: Do teachers find it useful, reliable, and actually supportive?

Reliability: Does it still work offline, on entry-level devices, and with spotty power?

Sustainability and scalability: Can it scale without endless funding or external support?

When these pieces come together, we learn not just what works but what lasts.

Evaluation types: Different paths to evidence

When it comes to proving what actually works, Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) are still the gold standard. The UK-based Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) notes RCTs are “the optimal and least biased method” for estimating causal impact. But they’re also expensive and slow, and AI developers and users don’t exactly wait around.

That’s why researchers use a mix of methods to balance speed and rigor; every choice trades off causal certainty, speed, and cost. Think of evaluation as a spectrum, from well-designed RCTs on one end to scrappy classroom pilots on the other. The middle ground (quasi-experimental and mixed-method studies) tells us not just if something works, but why. Together, they help developers and funders build confidence early and strengthen evidence as tools mature.

Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs):

The purpose is to establish causal evidence (does the tool cause learning gains?)

The tradeoff of high rigour is that it can make the evaluation slow and expensive.

Quasi-Experimental Designs (QEDs):

The purpose is to determine impact when random assignment isn't feasible using statistical methods or regression adjustments.

The tradeoff is getting only moderate rigour with a higher risk of confounding factors.

Adaptive/Iterative Tests:

The purpose is to provide quick feedback loops using data to rapidly refine and improve the tool, a common approach used in software development.

The tradeoff is lower rigor that can measure and confirm user engagement rather than the tool’s actual impact on learning outcomes.

Process Evaluations:

The purpose is to surface real-world insights on usability, teacher training, and implementation barriers.

The tradeoff is that while you get rich qualitative data you cannot determine the impact on learning outcomes.

Rapid Pilots:

The purpose is to conduct cheap, fast trials in small contexts to inform early go/no-go decisions.

The tradeoff is that while you get high speed you get lower rigour and less generalizable results.

A tiered approach means we don’t have to wait years for a verdict. Instead, we generate evidence early, build confidence gradually, and layer rigor over time as products stabilize.

Who evaluates matters, too. When developers grade their own homework, bias creeps in. Third-party partnerships, preregistered protocols, and open-data standards keep results real.

How benchmarks & evaluations fit together

Benchmarks and evaluations are two sides of the same coin. Benchmarks show us what “good” looks like – how a model performs on comprehension, pedagogy, or multilingual tasks. Evaluations then take those top-scoring tools into real classrooms to see whether they actually deliver.

A simple evidence loop might look like this:

Define what matters: Set the technical and ethical guardrails for “good” AI.

Benchmark tools: Use context-relevant tests, such as pedagogy or local language benchmarks.

Shortlist top performers: Identify those that meet or exceed agreed thresholds.

Evaluate in classrooms: Test shortlisted tools in real contexts to see what works, for whom, and under what conditions.

Scale what works: Track cost, usability, and learning impact as products grow.

Re-test and refine: Keep validating as models evolve to make sure they remain safe, effective, and equitable.

The goal is to keep innovation and evidence moving in sync – fast enough to keep up with AI’s pace, but grounded enough to build trust.

What can funders do to encourage benchmarking & evaluation?

Funders have a unique chance to do more than finance pilots. With smart co-ordination, they can help the whole field move from one-off projects to a shared learning ecosystem.

Here are 5 practical ways to lead:

Set shared standards. Bring partners together to define common benchmarks for pedagogy, local language support, safety, and accessibility. Think of it as an open “test bed” for AI in education, a public good that everyone can use.

Require independent evaluation. Keep developers and evaluators separate to reduce bias. Support third-party evaluation hubs, open protocols, and transparent data-sharing so findings stay credible and reusable.

Support faster learning cycles. Pair long-run RCTs with quicker, adaptive trials that can evolve alongside product updates. The goal is to learn fast without cutting corners.

Create comparable scorecards. Track learning outcomes, cost-effectiveness, teacher trust, reliability, and safety across projects to see where investments add the most value.

Invest in open infrastructure. Fund shared datasets, leaderboards, and evaluation tools that can be localised for low-resource contexts. These public goods raise the bar for everyone.

Together, these moves can help the field shift from scattered pilots to a connected, cumulative body of evidence - one that keeps pace with AI while protecting learners and teachers.

Just like in medicine or space travel, progress depends on testing. Benchmarks and evaluations aren’t red tape; they’re the guardrails that let us move fast and safely.

This edition of the Learning Futures Briefing was led and written by Shabnam Aggarwal, with contributions from Dr. Robin Horn, Ayesha Khan, Sara Cohen, and Faizan Ul Haq.